Dr Caroline Upton and Dr Sarah Johnson, University of Leicester

Understanding pastoral resilience

Pastoralism is the most important food production system in dryland environments, supporting some 500 million people globally. Such ecosystems depend on seasonal and sometimes highly unpredictable rainfall. They are increasingly subject to pressures cutting across sectors and research disciplines, associated with urbanisation, agriculture, conservation, mining, tourism, and land privatisation/enclosure. As a result, contemporary pastoralists face significant challenges. ‘Resilience-building’ features prominently in development strategies, to enable communities to cope with socio-environmental change, but ‘resilience’ is itself a surprisingly complex issue.

According to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, resilience is “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner”. However, such definitions do not necessarily equate to pastoralists’ own experiences. What does resilience actually mean for pastoral communities, if anything? Is it about coping with changing environments and droughts, or the economics of everyday life? What role do governments play in setting relevant policies? How do pastoralists navigate these complex issues to manage their livestock and livelihoods?

With funding from UK Research Councils, we launched a project in 2016 to look critically at the challenges pastoralists face, and to try to bring fresh insights and approaches to ‘resilience’. We focused on Kenya and Mongolia, both countries with significant dependence on pastoralism, and comprised a highly interdisciplinary team of social and environmental scientists, remote sensors and anthropologists. Inclusion of NGOs and university partners in both countries was critical to the project’s success. Activities included workshops, Kenya-Mongolia exchanges, and co-research with selected pastoralist communities, using a variety of innovative methods.

Our activities were shaped by previous evidence that greater emphasis was needed on understanding local meanings of and aspirations for ‘resilience’, linked to environmental histories and contexts. Gaps in understanding how pastoralists’ own aspirations could best be supported by external (e.g. government and donor) interventions were a further important issue.

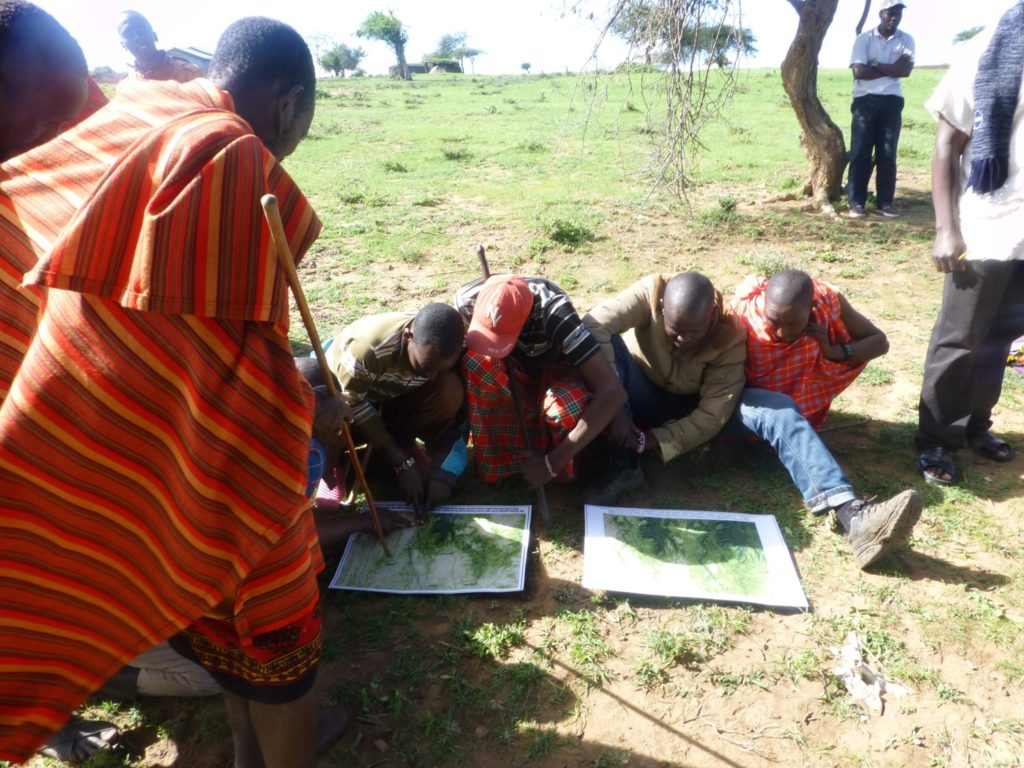

Other key challenges were in understanding pastoralists’ information needs. The recent availability of new, high resolution satellite data gave us a moment of opportunity, offering detailed and frequently updated information on pasture condition and water availability. To date, there has been limited work on understanding how such data may be made available to and used by pastoralists in ways that support their needs.

Through our project, we worked with local pastoralists to explore these issues and challenges. Pastoralists took a leading role in explaining resilience from their own perspectives, by developing their own photographic commentaries with a technique called PhotoVoice. Older pastoralists told us ‘Resilience Stories’, through which they explained their own histories, livelihood strategies, and experiences of environmental change.

Outcomes and Impacts

Our interdisciplinary work highlighted complex aspects of resilience, which may otherwise have remained hidden. For example, in Mongolia, new monetarisation of pasture access emerged as a key factor in shaping current resilience strategies. This acted in diverse ways and according to pastoralists’ social networks and socio-economic status, with important implications for future policy.

One of our greatest challenges was to understand how pastoralists viewed their own landscape, and how this could best be reflected in new mapping products, to supplement traditional decision-making strategies. Furthermore, data regarding current water and pasture condition needed to be coupled with an understanding of the politics of resource access and local landscape descriptors, to prove beneficial.

One of the main outputs of the project, the PhotoVoice book, is being used as a basis for pastoralists’ engagement with local government decision-makers in policy development. The team also developed a policy brief which is being disseminated through global online pastoralist networks.

This video, made by our local NGO partner, Stanley Kimaren, explains how we worked with local communities and the impact of the project in Kenya.

The work has also been hugely successful in supporting the success of a previous project delivering improved resilience for Mongolian herding communities using satellite derived services funded by the UK Space Agency, to develop services to improve resilience for pastoralists in Mongolia. The project partners directly with key Mongolian government agencies and pastoralist communities.

This research project was jointly funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund grant from the Natural Environment Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, and Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Image credit: Caroline Grondin via Unsplash